In the ever-evolving landscape of cloud-native computing, organizations are constantly seeking ways to balance security, performance, and operational efficiency. Traditional containers have revolutionized application deployment with their lightweight nature and rapid scaling, but they often fall short in providing robust isolation, especially in multi-tenant environments. On the other hand, virtual machines offer strong security boundaries but at the cost of higher resource overhead and slower startup times. This is where innovative approaches like running Kubernetes pods within lightweight micro-virtual machines come into play, bridging these gaps effectively.

This comprehensive guide delves into everything you need to understand about this technology, from its foundational concepts to practical implementations, benefits, challenges, and future directions. Whether you’re a platform engineer, security architect, or DevOps professional, you’ll gain insights into how this paradigm enhances Kubernetes workloads.

Understanding the “Why”: The Limitations of Traditional Models

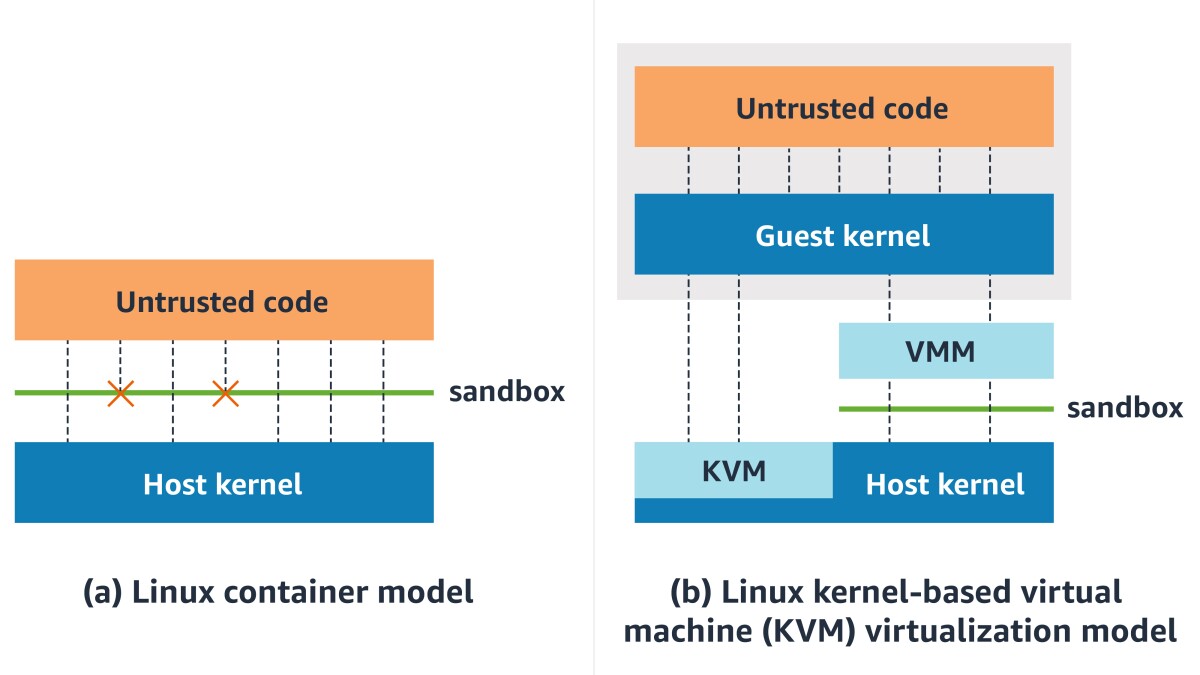

To appreciate the value of advanced isolation techniques, it’s essential to first examine the shortcomings of conventional deployment models. Traditional containers, powered by technologies like Docker, share the host operating system’s kernel. This shared kernel approach enables efficiency and speed but introduces significant security risks. For instance, a vulnerability in one container could potentially allow an attacker to escape and compromise the entire host or other containers running on it. This is particularly problematic in multi-tenant setups where different teams or customers share the same infrastructure, leading to “noisy neighbor” issues where one workload’s resource consumption affects others.

Virtual machines (VMs), in contrast, provide hardware-level isolation by running separate guest operating systems on hypervisors like KVM or Hyper-V. Each VM has its own kernel, making it much harder for breaches to propagate. However, VMs are resource-intensive, requiring dedicated memory and CPU allocations even when idle, and they boot slowly compared to containers. This makes them less ideal for the dynamic, ephemeral nature of modern microservices architectures.

The need for a hybrid solution arises in scenarios demanding VM-like security without sacrificing container agility. This is precisely the motivation behind PodVM, which combines the best of both worlds by encapsulating Kubernetes pods within microVMs – lightweight VMs optimized for container workloads. These microVMs strip away unnecessary components, resulting in faster startups and lower overhead while maintaining strong isolation boundaries.

Demystifying the “What”: What Exactly is PodVM?

At its core, PodVM represents a shift in how Kubernetes manages workloads. Instead of running pods directly on the host kernel via a container runtime like containerd or CRI-O, this approach launches each pod inside a dedicated microVM. A microVM is a minimalistic virtual machine that includes only the essential kernel and user-space components needed to run containers, often based on technologies like LinuxKit or unikernels.

In Kubernetes terms, a pod is the smallest deployable unit, consisting of one or more containers that share storage, network, and lifecycle. With PodVM, the pod becomes virtualized at the hardware level, enforced by a hypervisor. This setup is achieved through specialized runtimes that integrate seamlessly with the Kubernetes Container Runtime Interface (CRI). Users specify this behavior in the pod manifest using a RuntimeClass, which tells the scheduler to select nodes equipped with the appropriate runtime.

The result is enhanced security: each pod operates in its own isolated environment, preventing kernel exploits from affecting the host or neighboring pods. Yet, it retains the familiar Kubernetes API and tooling, so developers don’t need to change their workflows. This makes it an attractive option for environments requiring compliance with standards like PCI-DSS or HIPAA.

To illustrate, consider a typical deployment: A developer deploys a pod via kubectl. The Kubernetes control plane schedules it to a worker node. Instead of spawning containers directly, the node’s runtime boots a microVM, initializes a lightweight OS, and then runs the containers inside it. Networking and storage are proxied through the hypervisor, ensuring compatibility with Kubernetes features like services, ingresses, and persistent volumes.

The Architecture: How It Works

Diving deeper into the mechanics, the architecture revolves around key components. The process begins with the Kubernetes API server receiving a pod creation request. If the pod spec includes a RuntimeClass pointing to a virtualized runtime, the scheduler assigns it to a compatible node.

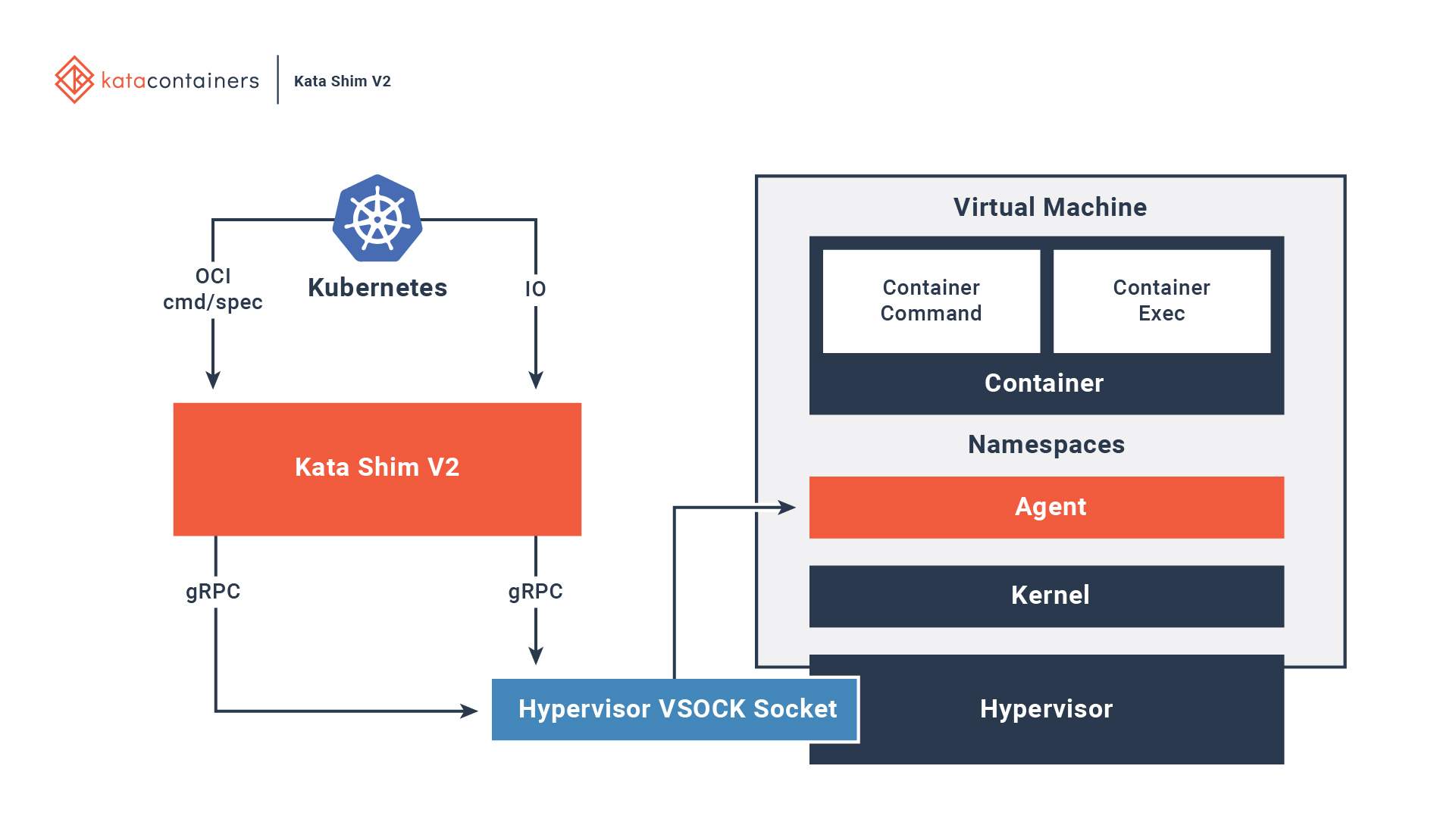

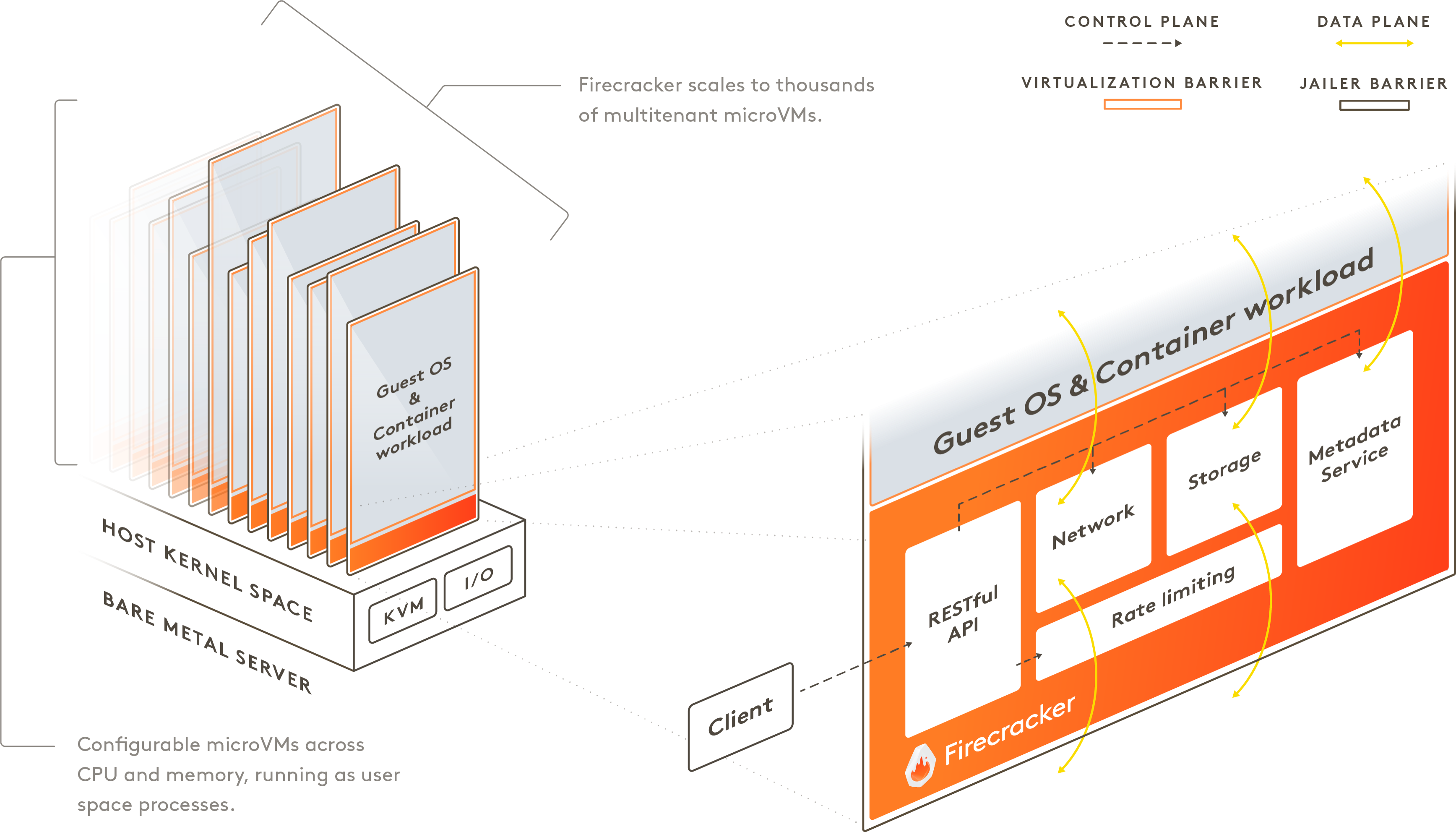

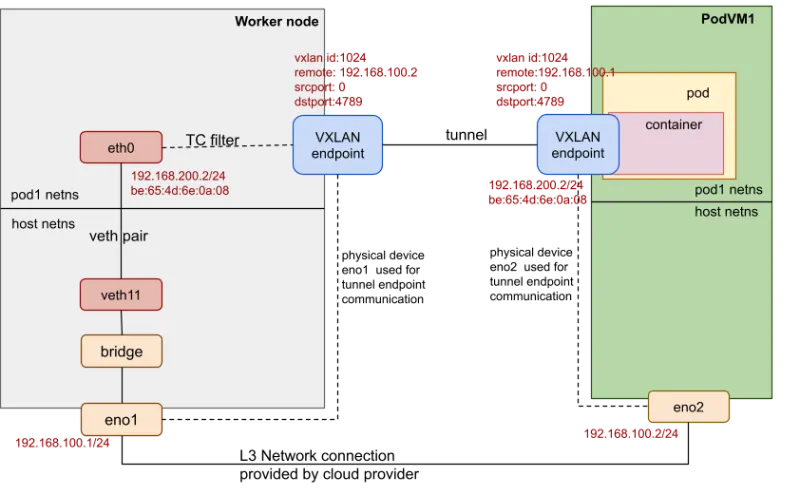

On the node, the CRI-compatible runtime – such as Kata Containers or one based on Firecracker – takes over. It interacts with a hypervisor (e.g., QEMU or KVM) to launch a microVM. This microVM boots a minimal guest kernel, sets up virtual devices for CPU, memory, and I/O, and then starts an internal container runtime to execute the pod’s containers.

Key elements include:

- Hypervisor Layer: Provides hardware virtualization, isolating the guest from the host.

- Guest Kernel: A stripped-down Linux kernel handling only necessary syscalls.

- Virtual Devices: Emulated hardware for networking (e.g., virtio-net) and storage (e.g., virtio-blk), ensuring low-latency access.

- Proxy Mechanisms: Tools like vsock or virtio-vsock for communication between the host and guest.

This setup minimizes attack surfaces by reducing the code running in the guest and leveraging hardware features like Intel VT-x or AMD-V for efficient virtualization. Performance benchmarks show that while there’s a slight overhead (typically 5-20% in CPU and memory), it’s far less than traditional VMs, with boot times under a second for microVMs like Firecracker.

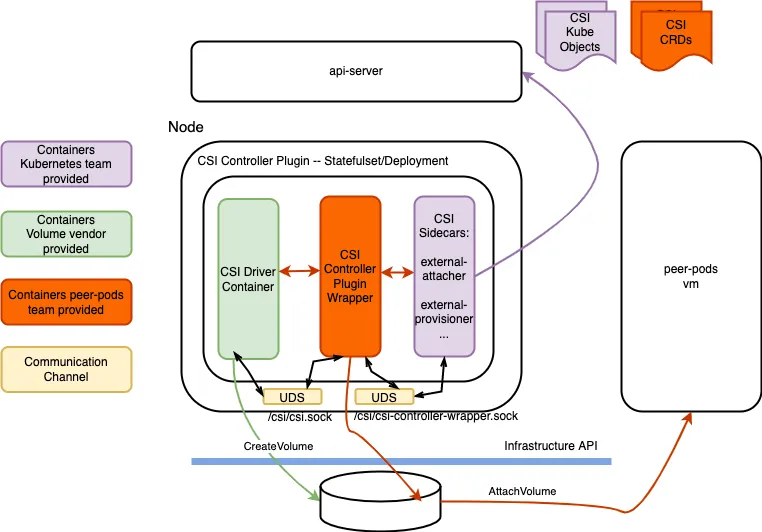

In practice, integration with Kubernetes networking plugins (e.g., Calico, Cilium) and storage (e.g., CSI drivers) remains transparent, allowing pods to communicate as usual.

What is a Pod in a VM?

The concept can be understood in two primary contexts. First, in traditional Kubernetes, a pod runs on a VM-based node, where the entire worker node is a VM hosted on a cloud provider like AWS EC2 or Google Compute Engine. Here, the pod shares the VM’s kernel with other pods on the same node.

In contrast, the PodVM model inverts this: the pod itself is encapsulated within a dedicated microVM, while the node might be bare metal or a larger VM. This per-pod virtualization ensures stronger isolation, as each pod has its own kernel instance. Technologies like Red Hat’s peer-pods extend this by offloading pods to remote VMs for even greater flexibility in hybrid clouds.

This distinction is crucial for security-sensitive workloads, where per-pod isolation prevents lateral movement in case of a breach.

What is a Pod Used For?

In Kubernetes, a pod serves as the atomic unit of scheduling and scaling. It encapsulates one or more containers that need to co-locate and share resources, such as a web server container alongside a logging sidecar. Pods are used for:

- Deploying single-instance applications.

- Grouping helper containers (e.g., proxies, adapters).

- Managing ephemeral jobs or cron tasks.

- Ensuring atomic updates in deployments.

Without pods, Kubernetes couldn’t abstract away the complexities of container orchestration, making it easier to handle networking, storage, and lifecycle management.

What is a Pod vs. a Container?

A container is a standalone, executable package of software that includes everything needed to run an application: code, runtime, libraries, and dependencies. Tools like Docker create containers, which are isolated at the process level using namespaces and cgroups.

A pod, however, is a Kubernetes-specific construct that wraps one or more containers. It provides shared namespaces for network, IPC, and PID, allowing containers within the same pod to communicate via localhost. Pods also manage shared volumes and define restart policies. Essentially, while a container is the runtime unit, a pod is the deployment and scaling unit in Kubernetes.

Is a Kubernetes Pod a VM?

No, a standard Kubernetes pod is not a virtual machine. It’s a logical grouping of containers running on the host kernel, using Linux namespaces for isolation rather than hardware virtualization. This makes pods lightweight but susceptible to kernel-level attacks.

However, in the PodVM paradigm, a pod effectively behaves like a VM by running inside a microVM. The pod abstraction remains the same, but the underlying execution environment shifts to virtualized hardware, combining container portability with VM security.

The Key Technologies Powering the Ecosystem

Several open-source projects drive this innovation:

- Kata Containers: An OCI-compliant runtime that uses hypervisors like QEMU to run containers in lightweight VMs. It supports Kubernetes via RuntimeClass and offers features like guest agent for management.

- Firecracker: Developed by AWS, this VMM (Virtual Machine Monitor) is designed for secure, multi-tenant serverless workloads. It boots in milliseconds and uses KVM for isolation, making it ideal for per-pod VMs.

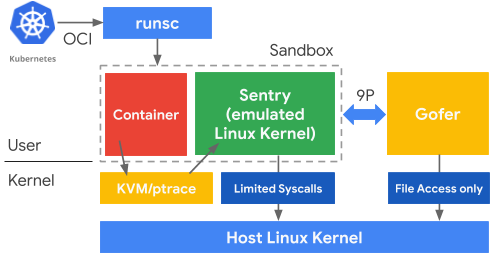

- gVisor: Google’s user-space kernel that intercepts syscalls, providing a sandbox layer without full virtualization. It’s a lighter alternative for scenarios where full VM overhead is unacceptable.

Other tools like Rust-VMM and Cloud Hypervisor contribute to the ecosystem, enabling custom microVM builds.

Use Cases: Where Does It Shine?

This technology excels in environments prioritizing security:

- Hostile Multi-Tenancy: In shared clusters, it prevents tenant cross-contamination, ideal for SaaS providers or public clouds.

- Regulated Industries: Finance, healthcare, and government sectors benefit from compliance-friendly isolation for sensitive data.

- Legacy Modernization: Migrating monolithic apps to containers while adding VM security layers.

- High-Value Targets: Protecting workloads handling cryptographic keys or AI models from advanced threats.

Real-world examples include AWS using Firecracker for Lambda and Fargate, and Red Hat OpenShift employing sandboxed containers for enhanced isolation.

Challenges and Considerations

Despite its advantages, adoption involves trade-offs:

- Performance Overhead: MicroVMs consume more resources than native containers, potentially reducing node density by 10-30%.

- Startup Latency: While optimized, booting a microVM takes longer than spinning up a container, affecting auto-scaling in high-traffic scenarios.

- Operational Complexity: Managing hypervisors and guest kernels requires additional expertise and monitoring tools.

- Compatibility: Not all hardware supports nested virtualization, and some legacy apps may need tweaks.

To mitigate these, start with pilot workloads, use auto-scaling groups, and leverage managed services from providers like AWS EKS or Google Kubernetes Engine.

The Future of PodVM

Looking ahead, integration with confidential computing – using hardware like AMD SEV or Intel SGX – will enable “confidential pods” where memory is encrypted in use. This addresses emerging threats like side-channel attacks. Additionally, as edge computing grows, microVMs will support low-latency, secure deployments in IoT and 5G networks.

Advancements in unikernels and WebAssembly could further reduce overhead, making virtualized pods the default for security-conscious organizations. With Kubernetes evolving to natively support these runtimes, the line between containers and VMs will continue to blur.

Conclusion

PodVM marks a significant evolution in cloud-native security, offering VM-grade isolation within the Kubernetes framework. By addressing the vulnerabilities of shared kernels while preserving agility, it empowers teams to build resilient, compliant applications. As threats become more sophisticated, adopting such hybrid models will be key to staying ahead.

Whether enhancing multi-tenancy or securing regulated workloads, this approach provides a robust foundation for modern infrastructure.

FAQ

What are the main benefits of using microVMs for Kubernetes pods?

The primary advantages include enhanced security through hardware isolation, better multi-tenancy support, and compliance facilitation without major workflow changes. It reduces risks like container breakouts and noisy neighbors.

How does it impact performance compared to standard containers?

There’s a modest overhead in CPU and memory (5-20%), but optimizations in tools like Firecracker minimize this. Startup times are sub-second, making it suitable for most applications.

Can I use it with existing Kubernetes clusters?

Yes, by configuring RuntimeClasses and installing compatible runtimes like Kata Containers. It’s compatible with major distributions like OpenShift and EKS.

What are some alternatives to full microVM approaches?

Options include gVisor for syscall interception or namespace hardening with seccomp and AppArmor for lighter isolation.

Is it suitable for all workloads?

It’s best for security-critical ones; for performance-sensitive apps, benchmark first to assess overhead.

How do I get started with implementation?

Begin by installing a runtime like Kata on your cluster, define a RuntimeClass in your pod specs, and test with sample deployments. Refer to official docs for each tool.